Rose Nneoma Abba

Hi,

I’m an artist and researcher building a life where I get to produce, manage, and circulate beauty and knowledge, while making a positive difference in how the pursuit of knowledge is valued in post-colonial societies.

Welcome to my workshop, Studio Styles.

As a secondary school student, I had committed myself to Chinua Achebe’s calling in his 1998 book Home and Exile to “others who may believe with me that a universal civilization is nowhere yet in sight” to join the “war against dispossession” through the “re-storying” of colonized people.

Then, as an undergraduate studying History, Literature, and Cultural Theory in London, I hit a wall when I found that I could not access as much historical and cultural data as I needed to explore the questions I had about my Nigerian society. Out of the frustrations I encountered over similar limits during my master's degree in History at Oxford, Studio Styles was born. In its first year (2020), I produced documentary projects on architecture, the built environment, religious and youth cultures in South-East Nigeria, in a double effort to make potential archival material as well as understand the barriers to documentary and archival production in Nigeria.

I returned to Nigeria after my master’s to embark on a four-year independent research project as Studio Styles, asking, ‘How are Nigerians making a living, finding belonging, and creating meaning in their lives today?’ In the process, I worked as a freelance journalist, researcher, and photographer with projects published and screened in the likes of the BFI (UK), LACMA (US), Art Jameel (UAE), The Republic (NG), Le Temps (CH), and Heinrich Böll Foundation (DE/NG). I also took up numerous fellowships at institutions such as the Royal African Society’s African Arguments (UK), Zeitz MOCAA (SA), DOCOMOMO International, the Open Society Foundations, and the Goethe-Institut Nigeria, through which I gained exposure to and experience in global arts and culture writing, research, production, preservation, and management.

❊

Through this four-year project of treating the everyday as archive, the informal as theory, and the personal as data, I saw a lot about how Nigerian life, the social, moral, spiritual, and imaginative economies are the immaterial engine driving the nation’s material conditions, its politics, and financial economy.

And the fundamental challenge—at the level of ideas—of Nigerian life that I am most concerned with and most equipped to address is disconnection: from one’s self, community, history, and the environment.

In response to this challenge, I’m working on a theory of knowledge as relational continuity: Life, Nigerian life with its webbing of informality especially, continually improvises intelligence. To know is to stay in rhythm with that improvisation, not to possess information. To pursue knowledge in this way is to engage in social healing, where healing is not about erasing wounds or returning to some pure state, but rather requires both contact and distance, rhythm and rest, and ultimately restoring our capacity to dig deep where we stand.

My current thinking owes a lot to Ayi Kwei Armah’s novel The Healers, Jacques Depelchin’s Silences in African History, Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and Tsitsi Dangaremba’s novel Nervous Conditions.

❊

The output of this four-year endeavour is a constellation of five prototype projects, each addressing the crisis of disconnection through a different register:

The Sweet Medicine Podcast, advocating for social healing through the humanities (funded through an Open Society Foundations Ideas Workshop Fellowship);

Restful, an anthology of essays and photographs by Nigerians on how they navigate stress in their intimate and social lives (funded by the Goethe-Institut Nigeria);

#CulturePays, a collaboratively produced nationwide survey and report on the economic realities of Nigerian creative and cultural practitioners;

Does Your God Sleep?, a documentary series on young Nigerians’ ideas about fear and God;

Our Bodies, Nigeria’s Ghosts, a memoir-documentary film on inherited rhythms of coloniality and resistance in today’s Nigeria (funded by the Goethe-Institut Nigeria’s Post-Memory, Post-Archive project).

❊

If any of this resonates and you’d like to gist about it, email me at hello@studiostyles.org.

Recent Projects

(outside Studio Styles)

In progress, seeking funding

321: The Republic of Grief (book and documentary project)

In December 2005, I lost my brother in the Sosoliso plane crash, one of three air disasters that killed 321 people in Nigeria between 2005 and 2006. I was eight years old. That moment became my initiation into what I call the Republic of Grief: a nation haunted by loss and numbed by state failure.

Over the past five years, I’ve been reflecting on my experience of that event and its aftermath. The first outcome of this reflection was my essay The Fire in My Memory, which won the inaugural Abebi Award in Afro-Nonfiction (2023) and was long-listed for the 2023 Wasafiri Life Writing Prize. Writing it opened an irresistible line of inquiry into how Nigerians create meaning of—and seek healing amid—the wounds the country inflicts on its people every day.

This is a project I hope to work on during the twentieth anniversary of those crashes (2025–2026). It explores the afterlife of those events as both personal and collective trauma—how Nigerians create meaning, memory, and accountability in the wake of negligence.

At its heart, 321 is an inquiry into the redemptive power of love, responsibility, and collective remembrance, and how, even after catastrophe, we keep trying to build a nation worth mourning for.

2025

Our Bodies, Nigeria’s Ghosts (film, 19’)

Our Bodies, Nigeria’s Ghosts confronts the afterlives of colonialism in present-day Nigeria, asking how power, punishment, community, and survival are inscribed in the body. Blending documentary, memoir, performance, and reimagined archival footage, it stages a dialogue between present and past, here and elsewhere.

At its core, the film is a study in rhythm: the inherited rhythms that shape our movements, the imposed rhythms of domination, and the chosen rhythms of resistance. Refusing to be confined to the languages of violence or erasure, the filmmaker turns to dance—to the body’s music—as an antidote. Dance becomes a declaration of presence, a refusal of silence, and an expression of ever-evolving indigenous movement that releases history’s ghosts from the mausoleums of “fixed ways”, carving space for fidelity to the now.

It was produced during the Goethe-Institut Nigeria's post-Memory, post-Archive fellowship (2024-2025).

Director bio:

Rose Nneoma Abba is an artist based in Enugu, Nigeria. Under the name ‘Immaculata’, her debut short film You Matter to Me premiered at the Royal African Society’s Film Africa festival 2022 and won the Rising Star Award at the 2023 Surreal 16 Film Festival. She holds a Master’s degree in History from the University of Oxford. Our Bodies, Nigeria's Ghosts is her second film.

Festival Screenings

Decasia Film Festival (Lagos, Nigeria) - Jul 2025

Status Mutato Festival (Jos, Nigeria) - Oct 2025

Cinema African Festival (Linz, Austria) - Nov 2025

Program Screenings

post-Memory post-Archive Workshop Showcase

Goethe-Institut Nigeria/National Film Corporation (Lagos, Nigeria) - Aug 2025

2022

You Matter to Me (film, 11’)

“A wholehearted conversation between an artist and her parents exploring their personal philosophies on joy and where to find it. All be it, joys complicated by the tensions and grief that come with life in Nigeria. Abba layers emphasis on community and everyday rituals with a playful soundtrack composed in the spirit of ‘00s Nollywood dramas that remind the artist of things we might overlook that matter most in the end.” - ArtXLagos 2025 film programming

The film was made with a grant from the ‘Creating Joy: Art, Refusal and the Worlding of Black Lives’ project- a radical digital space that explores Black diasporic life through artmaking.

Festival Screenings

ArtXLagos (Lagos, Nigeria) - Nov 2025

Plateau International Film Festival (Jos, Nigeria) - Dec 2024

S16 Film Festival (Lagos, Nigeria) - Dec 2023

‘HOME: A Piece of Us’ film exhibition, Exmouth Film Festival (Exmouth, UK) - Nov 2023

‘Love and War’, 27th Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur (Zurich, Switzerland) - Nov 2023

Enugu International Film Festival, Viva Cinemas (Enugu, Nigeria) - Nov 2022

'Beyond Nollywood: Wahala Dey' at Film Africa festival, BFI London (London, UK)- Oct 2022

Program Screenings

Screen in Transit (Abuja & Lagos, Nigeria) - Nov 2024

Fenmore Studios x Institut Français (Abuja, Nigeria) - Feb 2024

OTO film screening (Lagos, Nigeria) - Feb 2024

Film Diary NYC III (New York City, USA) - Dec 2023

The Library of Africa & the Africa Diaspora (Accra, Ghana) - Jun 2023

Pynk Prysm x Covent Garden’s The Garden Cinema (London, UK) - May 2023

Jameel Arts Centre (Dubai, UAE) - May 2023

Classics in the Park (Accra, Ghana) - Feb 2023

Family Film Club (Lagos, Nigeria) - Dec 2022

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles, USA) - Dec 2022

Watch on YouTube:

“[...] the commercial and cultural dominance of 1990s Nigerian cinema has left a lingering aesthetic mark. In «You Matter to Me», the old Nollywood aesthetic shows up in the film’s texture and its setting in a village in Eastern Nigeria. The short also discusses family, one of the main concerns of traditional Nollywood.”

2021

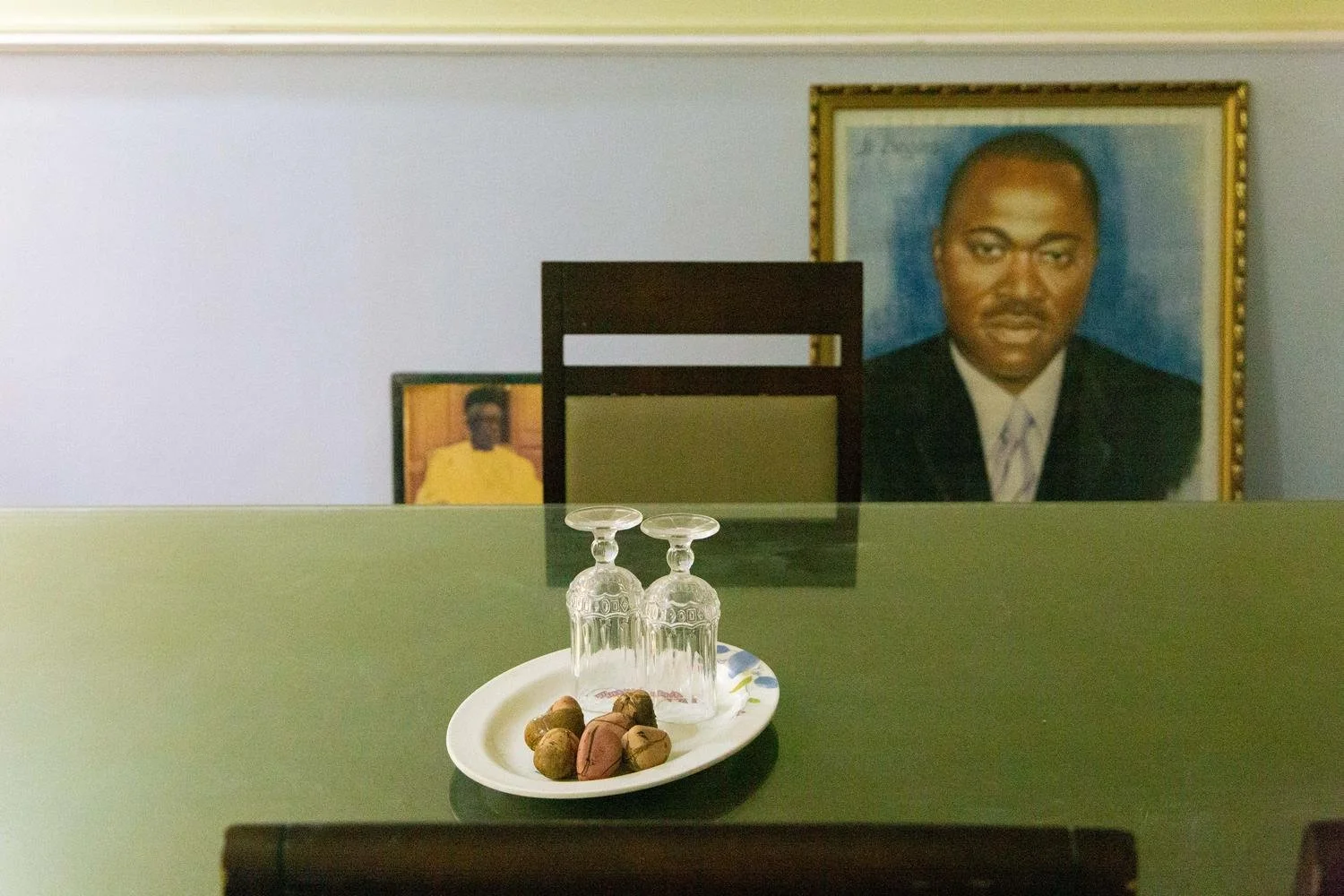

Sunrise Flour Mill (photography zine, Another Place Press)

Also available as part of the Another Place Press catalog in permanent acquisition at the St Andrews University Library, Scotland.

In 1983, the Enugu state government established the Sunrise Flour Mill with production lines for flour, semolina, and wheat.

Only two years later, in 1985, the mill went out of production as the industry could not survive the strain of an economic depression. The closing of the mill is one of the many instances of Nigeria’s deindustrialisation, a consequence of the forced abandonment of industrial policies induced by the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), which devastated many ‘developing’ economies around the world in the late twentieth century.

The mill has remained moribund for the past twenty-five years, in spite of efforts to reignite production in 1992 and 2013. Most recently, in 2013, in line with the federal establishment of a free trade zone in the state, the Enugu state government signed an agreement with a Vietnamese company, DVI Trading Services and Investment, to take over the Flour Mill for a period of 30 years. Yet, the mill remains defunct and the estate buildings out of use (except the living quarters). A few years ago, the administrative building in the estate suffered water damage, to add to the slow degradation it has suffered in its past 25 years of inactivity.

I shot these photographs of the building and its interiors to speak to the decay of Nigerian resources and capacity in the hands of consecutive administrations that continue to fail its potential. A flour mill that goes defunct after only two years of production, only to live for decades as an echo of its potential, is a metaphor for this period in Nigeria’s trajectory.